When Provence Met India

- Winifred and Evalyn

- Sep 13

- 6 min read

Over two years ago, I had a serendipitous meeting with Hiata, owner of Winifred & Evalyn. I was about to fly back to India, where my husband and I have spent about half the year for the least three. Her shop compelled me with it’s mix of Indian blockprint and French aesthetic, and serendipitously a friendship and work relationship was born.

I’m a newbie to the textile world and a not-so-newbie history lover, so I was fascinated to learn about the historically rich connection between Indian and French textiles. As all stories about colonial rule...it’s complicated.

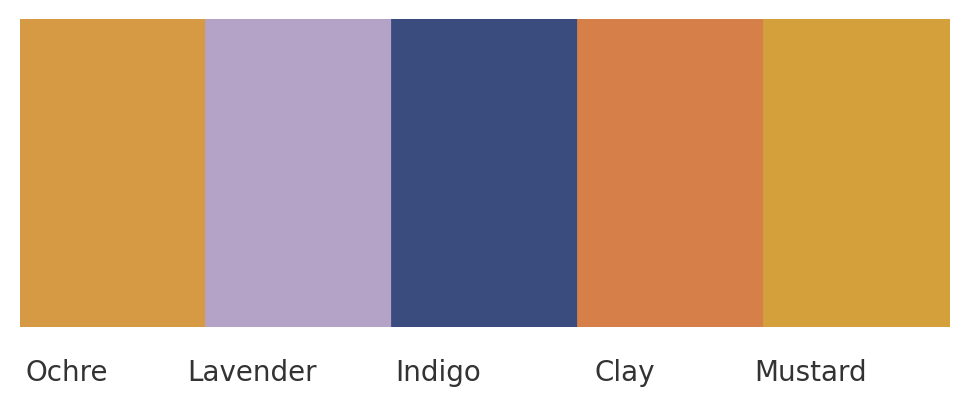

A quintessential view of a sun-filled countryside in the South of France: cheerful cottons dance on laundry lines, fluttering in the breeze. Their patterns: florals, vines, and sunbursts in ochre, crimson, and faded blue, feel distinctly Provençal. But they echo one of Provence’s most fascinating cultural exchanges. By the 18th century, the art of indiennes—Indian-inspired printed cottons—had become one of the defining features of Provençal design.

These designs weren’t just a current trend, but a revolution born from centuries of global trade, imperial ambition, artisan ingenuity, and the human desire to bring beauty into the everyday. The story of indiennes, as any cultural exchange (is it exchange? or takeover? another time, another post) is a story of influence and interpretation, of what happens when cultures collide, not just in conflict (and there was plenty of that) but in creativity (what happens when the big kids are fighting in the sandbox).

Ships, Spice and Cotton Dreams

The journey of indiennes begins in India, long before the French ever laid eyes on a printed cotton. By the early medieval period, India was already a textile powerhouse. Regions like Gujarat and the Coromandel Coast were famed for their fine cottons, hand-spun and dyed with natural pigments, and printed with intricately carved wooden blocks. Patterns ranged from tiny florals to elaborate narrative scenes, each infused with symbolism and precision.

(Left: Long Cloth from Coramandel Coast c 1720s Right: Gujarat Bed Cover, 18th century(Metropolitan Museum of Art)

These textiles weren’t just beautiful, they were practical, breathable, and vibrant, and amazingly for this period, dyes that didn’t fade. That was thanks to Indian mastery of natural dye chemistry: mordants, plant-based fixatives, and an intimate understanding of how color behaves on cloth. Indigo from Gujarat, madder from Bengal, black from iron-rich mud, and yellow from turmeric all made appearances. These fabrics were colorfast in a world where most dyes ran at the first wash. One source relates that a French trader claimed, “the dyes last as long as the cloth itself.” That was, quite frankly, magic.

By the 16th century, Indian cottons were being exported in huge volumes to Europe, the Middle East, and Africa via maritime trade routes. The Portuguese were early importers, but it was the Dutch and later the French East India Companies that really scaled the enterprise.

Meanwhile, a thousand years before the French even knew the word હેલો, the Northern States of Gujarat and Rajasthan were block-printing. Using hand-carved wooden blocks, artisans stamp intricate designs onto cotton or silk, one color at a time. The precision required is breathtaking, and many families have passed this skill down for generations. The motifs are symbolic—florals, vines, birds, stars—and often tied to regional identity. Jaipur, Bagru, and Sanganer are famous for this art, each with its own style and rhythm.

Inspired by these Indian textiles, Provençal printers developed their own blocks, often mimicking the layout and floral detail of indiennes but adapted to suit local tastes. Over time, they created a distinctly French interpretation of Indian elegance. The result is what we now call boutis or piqué in quilting, and Provençal cottons in tablecloths and clothing—where the hand of India is still visible in the echo of each flower.

And then…Marseille entered the chat: Marseille was France’s gateway to the Mediterranean. Through this bustling port came not just spices and porcelain but a cargo that would transform the aesthetic of French domestic life: bolts upon bolts of printed Indian cotton.

Banned, Bootlegged and Beloved

Indian cottons were a hit in France, but sometimes, too much of a good thing is…too much of a good thing. By the late 17th century, their popularity posed a threat to France’s domestic textile industries, especially wool and silk. Fearing economic ruin, Louis XIV issued the Great Prohibition in 1686, banning the import and even wearing of cottons.

But the ban didn’t kill the love affair. Instead, it drove it underground. Bootlegged indiennes circulated among the wealthy. Smugglers found creative routes. And artisans in France began secretly replicating the technique a.k.a. reverse engineering block printing, experimenting with dye recipes, and eventually producing their own "French" versions of Indian prints.

By the mid-18th century, the ban was lifted, and the pent-up demand exploded. Workshops popped up across southern France, especially in Provence, where warm light and rural traditions seemed to welcome these exuberant prints. The town of Tarascon became a hub of production. Here, the French indienne—named in homage to its Indian origin—was born.

These weren’t imitations. They were interpretations. (You just know there was a clever marketing team behind the whole ‘pent-up demand’ thing.) French artisans adapted the Indian designs to suit local tastes. More pastoral flowers, regional color palettes (ochre, rust, lavender), and motifs like olives or sunbursts began appearing. The art form became a hybrid: a meeting of India’s technical genius with Provence’s sensibility.

The Blockprint Bridge

This was all new to me, the textile novice, but I found the connection between Provence and India fascinating. They share a past, but also a craft kinship. And given that I am now working in retail and wholesale at Winifred & Evalyn where our vintage and hand-crafted items have roots in both India and France, the story of Indiennes has given further meaning to the world that we are building there.

And yes, imperialism played a role. There is an unevenness in how ideas and resources moved between the colonizer and the colonized. But within that complexity is also creativity: how one culture can influence another, not through erasure, but through transformation.

Block printing is a tactile, human process, whether in India or France. Wooden blocks are hand-carved, dyes are mixed in small batches, and fabrics are printed slowly, by eye and by feel. Each yard of fabric is the result of hundreds of hand-stamped impressions.

Both traditions rely heavily on natural dyes. In India, indigo is still grown and fermented into deep blue vats; madder roots yield warm reds; pomegranate peels lend soft golds. In Provence, ochres from the Roussillon cliffs were historically used to tint fabrics—yet another example of how earth and cloth are entwined.

Both regions have also preserved the idea that textiles are more than décor—they are daily art. Tablecloths, napkins, quilts, shawls… these items aren’t “special occasion” pieces; they’re part of life. They soften over time, carry stains and stories, and root us in place and memory.

The Ongoing Thread

Today, workshops in Provence and India still produce hand-printed fabrics, though they face growing pressure from industrial processes. Some traditions are being lost; others are being revived. There’s a growing global appreciation for these textiles, not just as pretty decor, but as vital expressions of cultural identity and shared heritage.

In our homes, we can celebrate that spirit by honoring the hand that made it, the plant that dyed it, the story that traveled. When you choose a linen with Provençal blooms or a hand-dyed napkin from Jaipur, you’re not just styling your table. You’re weaving together centuries of inspiration, resilience, and beauty. Your table tells a story.

Let your home be that kind of gallery. A place of layered stories. A place where threads connect not just fabric, but us, across time, place, and culture.

Thanks for reading Winifred & Evalyn! This post is public, so feel free to share it.

Comments